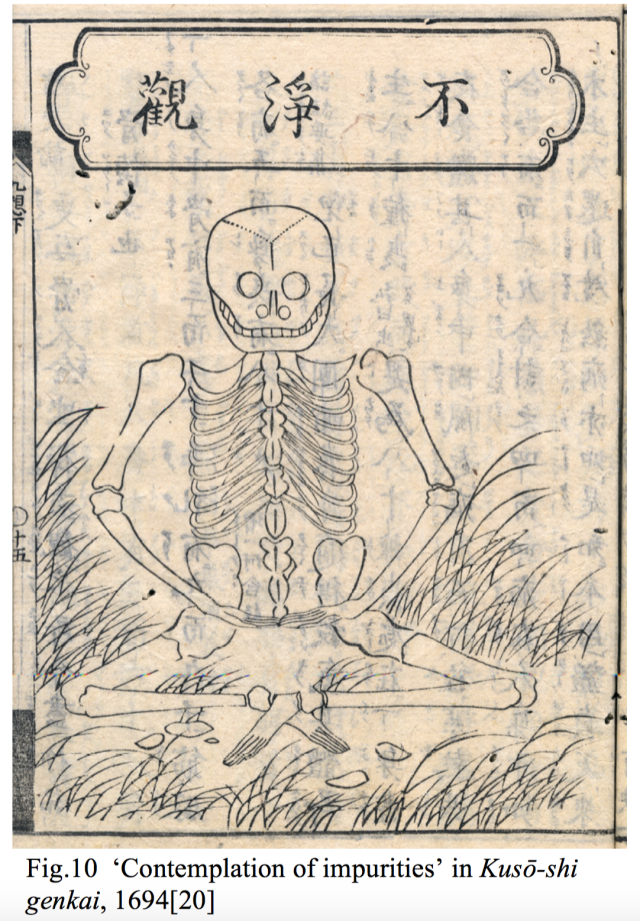

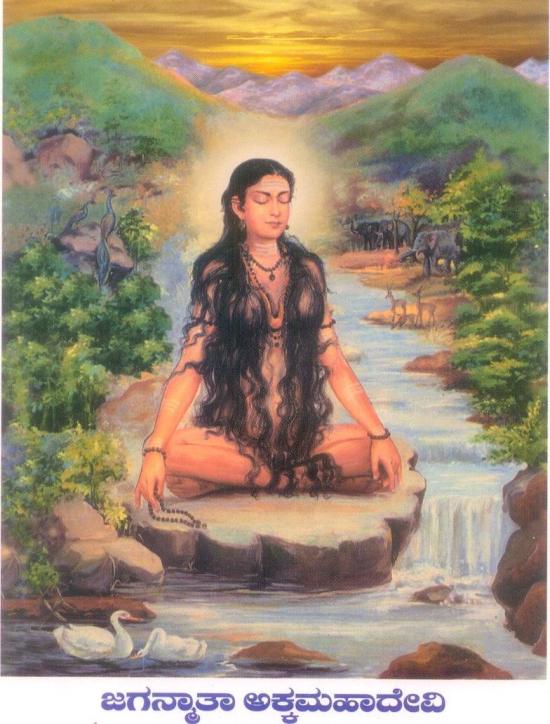

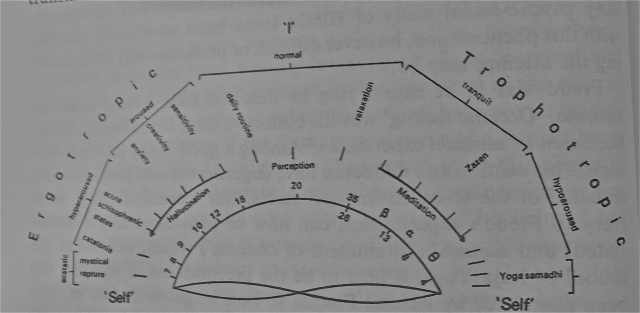

Though an ominous, violent phrase, I think this I think represents two ends of a similar means of attaining wisdom within the broader Dharmic tradition. Two which are at opposite ends of a particular horseshoe. 1) The intoxicated Caitanya-esque ecstatic dancing, music, or trance (embodied in most epitomized form by the heterodox, antinomian and anti-textualist Baul tradition) on the one hand, and 2) The almost inhuman, absurdist form of samadhi of Chan/Zen Buddhism on the other, which produced the brutal, piercing line from which this post derives its title. Theoretically, the two share a genealogical origin in conjoined tantric traditions of Sahaja/Sahajiya Buddhism/Vaishnivism respectively. See the below diagram, with Bauls occupying the far left and Zen occupying the far right of the diagram. See the following quotation for a Chan/Zen mode of describing this condition.

An eight-sided grinding disk is the large millstone which is turned by an ox or donkey. The idea that such an object was flying and cutting through the universe was something beyond common sense during the latter portion of the Kamakura period (1185–1333). There were intense debates on which form of Buddhism was superior: the established forms of Mahayana Buddhism or the newly imported Zen Buddhism. Scholars of the established Buddhist doctrine, with the intent to “crush” the newly arrived Zen Buddhism, debated Myocho Shuho who represented the Zen Buddhism side. (Later the Imperial Court honored Shuho by awarding him the highest title of Daito, Kokushi.) The scholars, after many debates, questioned Shuho: “Zen discourses intimate kyo gai betsu den [kyo=teaching; gai=outside; betsu=separate; den=communication]. What is the meaning of that phrase?” Shuho’s instant answer was “Octagonal grinding disk cuts through the universe.” The meaning of this phrase is that regardless of how well one intellectually understands the doctrine or dogma, without actual experience the understanding remains only on the surface. Deep attachments, delusions, intellectual understanding of good or evil; stubborn self-centered ideas and teaching through sutras: they who assume they are erudite scholars can be smashed into pieces but spiritual activity is totally free. Thus this statement ended the discourse and debates between the established Buddhist sects, and Zen Buddhism consequently gained a foothold in Kyoto.

The sagacity of this ichigyo mono made Zen Buddhism acceptable to other Buddhist scholars, and Daito, Kokushi since then has become greatly respected. The goal in Zen is to search for the truth with complete disregard for scholarly dialogue or one’s station in life.

In the work at left by Gengo Akiba Roshi, the subtitle is “Furyu Monji.” This means “not depending upon literature,” and is one of the phrases in traditional Chinese ideograms that explain the characteristic nature of Zen Buddhism. Other such phrases are Kyo gai betsu den meaning “extra- curricular or outside the teaching of sutras”; Jiki shi jin shin meaning “directly reaching to the heart and soul of that person”; and Ken sho sei butsu, meaning “rediscover the existing Buddha nature within oneself.” One must surpass or go beyond doctrine and the language from the teacher, and di- rectly connect with the spirit within. The student must take the mentor’s teaching and then internalize and digest it. Then it becomes an intrinsic part of heart and soul and allows each individual to grasp the core of Buddhist teaching in order to open the passage to satori. A simple way of saying this is to point your finger to your heart and it is the Buddha.

156-157, SHODO The Quiet Art of Japanese Zen Calligraphy