The Maldives are not a country we typically associate with Buddhism. Currently, it is primarily known to the West as a culturally denuded vacation dystopia/utopia catering to the cosmopolitan elite, though in reality, it also exists alongside a somewhat extremist Islamic state. A double whammy to ensure the cultural irrelevance of anything preceding even early modernity.

The paucity of the noticeable historical impact of Buddhism vis a vis Islam in the Maldives is actually one of the most severe I’ve ever studied, of any formerly Buddhist society. Typically those who mourn over the loss of such cultural zones reference Afghanistan, perhaps northern India, Bactria, Indonesia or elsewhere in Central Asia, or Southest Asia. But the elimination of Buddhism (and Hinduism for that matter) in the Maldives is shockingly total, not only in terms of population but also in terms of archeological evidence and even historical memory. This really is not something I’m making up. In the words of Hassan Ahmed Maniku (from CONVERSION OF MALDIVES TO ISLAM, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Sri Lanka Branch , 1986/87, New Series, Vol. 31 (1986/87), pp. 72-81):

Unlike any other country, when Maldives accepted Islam it was a complete acceptance. No trace of any other religion was left. Vestiges of whatever form of worship that existed prior to such acceptance was completely erased from view.

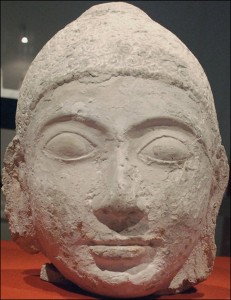

Whatever scraps escaped this storm are still under threat up until modernity. In 1959 the below pictured Buddhist statue was discovered in an excavation. It had clearly been intentionally buried to escape the wave of destruction that swept over the Maldives in the immediate aftermath of its conversion to Islam.

Almost immediately upon discovery, the statue’s head was smashed off, and most of the brittle torso was reduced to fragments. Below is the remaining head in the National Museum, after undergoing some restoration. Though given what happened in 2012 (see below) I am unsure of its current fate.