Continuing in my trend of alternative takes on Hindu texts…

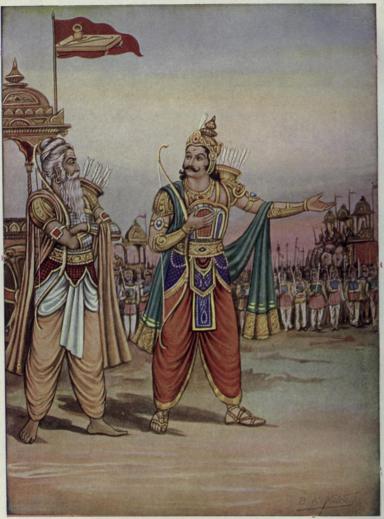

“Arjuna, having thus spoken on the battlefield, cast aside his bow and arrows and sat down on the chariot, his mind overwhelmed with grief.” -(Chap 1 Verse 46)

“Arjuna that chastiser of enemies said: I shall not fight O Krishna, and became silent.” (Chap 2 verse 9)

“Arjuna, having thus spoken on the battlefield, cast aside his bow and arrows and sat down on the chariot, his mind overwhelmed with grief.”

But unfortunately, the story doesn’t end there.

At the start of the Bhagvad Gita Arjuna is faced with a dilemma. On the one hand he is reluctant to enter into a war which is likely to cost the lives of most of his family, friends, respected elders, along with at least 4 million of his own citizens. On the other hand he also has moral duties as a warrior, and as a righteous person. According to the traditional interpretation the dilemma is resolved when Arjunas objections are defeated by the Divine Krishna’s appeals to selfless dedication to duty, (and the revelation of his Universal Form and the mystic wisdom that comes with it).

Seen in another light, this is the story of a rational, nonviolent man who gets persuaded, and frightened into obeying the whims of a mystical and powerful supernatural entity— Krishna. As a result of listening to Krishna’s advice he goes to war resulting in millions of deaths including almost his entire family. Most tragically, Arjuna loses his beloved 15 year old son Abhimanyu, who he loved deeply. Arjuna’s eventual victory is pyrrhic. He gains a kingdom he didn’t want all that badly, and loses many human relationships which he valued highly. He gives up a higher value in favor of a lower value– a fruitless sacrifice. As such, in the later chapters of the Mahabharata there is very little celebration of the victory at Kurukshetra. Instead sorrow and despair dominate the psyches of Arjuna and all the Pandava brothers.

This interpretation makes chapter 1 of the Gita the most noteworthy (Chapters 2 and 3 also contain some gems, but Arjuna’s defiance tends to fizzle out as the text goes on). Most readers go into this chapter under the preconception that Arjuna is wrong. It is read mostly as a preface to Krishna’s later statements. I implore readers to take this chapter seriously, because in fact the objections which Arjuna raises here are never adequately addressed by Krishna.

Arjuna, while he still retains his nonviolent instincts presents his argument against going to war. Despite being overwhelmed by grief and distress he repeatedly states that the kingdom, divine reward, or happiness which would result from winning the battle are simply not worth the resulting deaths:

“O Krishna, of what value are kingdoms? What value is living for happiness if they for whom our kingdom, material pleasure, and happiness is desired: preceptors, fatherly elders, sons; and grandfatherly elders, maternal uncles, fathers in law, grandsons, brothers in law, and relatives are all present on this battle field ready to give up their kingdoms and very lives? O Krishna even if they want to take my life I do not wish to take their lives. O Krishna what to speak for the sake of the earth, even for the rulership of the three worlds; in exchange for slaying the sons of Dhrtarastra what happiness will be derived by us?” (Chap 1 verses 32-35)

“How by slaying our own kinsmen will we be happy?” (Chap 1 verse 36)

“Alas how strange it is that we have resolved to commit great sin. Just because of greed for royal luxuries we are prepared to slay our own kinsmen.” (Chap 1 verse 44)

“It is better to live in this world by begging, without slaying our great and elevated superiors; otherwise by slaying our superiors the wealth and pleasurable things we are bound to enjoy will be tainted by blood.” (Chap 2 verse 5)

“Even if the sons of Dhrtarastra armed with weapons in hand slay me unarmed and unresisting on the battlefield that would be considered better for me.” (Chap 1 verse 45)

Arjuna seems relatively rational here. He engages in cost benefit analysis. He shows his preference for nonviolence over power, and family over material greed.

Krishna counters this with a blind appeal to duty but why should Arjuna adhere to his martial duty if there will be no perceptible gains to any party? According to Krishna doing one’s duty is inherently moral irrespective of the consequences so long as it is done with dedication to God. The idea that detachment from consequences is ideal becomes a persistent theme in the Gita. To be sure, selfless or detached action is useful in many avenues of life. But should we really ignore consequences when millions of lives are at stake?

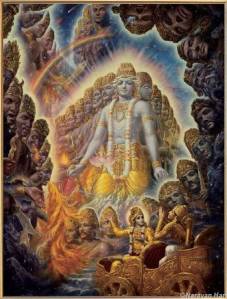

Eventually Krishna reveals his Universal Form to Arjuna. In Chapter 11 verse 23 Arjuna says “O mighty armed one, seeing Your magnificent form of manifold faces and eyes, manifold arms, legs and feet, manifold stomachs and manifold terrifying teeth; all the planets tremble in fear and so do I”. After this frightening episode, Krishna’s suggestions become more forceful and sometimes take on the form of commands.

“O mighty armed one, seeing Your magnificent form of manifold faces and eyes, manifold arms, legs and feet, manifold stomachs and manifold terrifying teeth; all the planets tremble in fear and so do I”

In the end, Arjuna succumbs to Krishna’s advice and fights. His teacher Drona, his son Abhimanyu, his grandfather Bhishma, his brother Karna, and innumerable others all die. After the battle, Arjuna repeatedly expresses remorse about his actions, and why wouldn’t he? Prior to the battle he made his preference for familial bonds over winning a kingdom perfectly clear. Yet, he followed Krishna’s advice to the letter for which he paid a heavy price.

How have so many thousands of years passed with nobody noticing that in this instance, Krishna gave profoundly poor advice? From a rights theorist perspective, Arjuna made the wrong choice because although he killed plenty of guilty people, innocents (i.e. draftees) also died. From a utilitarian perspective he made the wrong choice because he caused an enormous amount of unnecessary suffering and pain. From a rational egoist perspective he made the wrong choice because the decision did not serve his interests or advance his goals. Indeed, the only perspective from which Arjuna made the right choice is that of Bhagavad Gita devotionalist-duty ethics, whereby doing one’s duty as a devotional practice without thought for one’s own desires or the consequences of one’s actions overrides all other concerns.

The Gita can be read as the story of a peaceful rational man, reluctant to send 4 million men many of whom he loved to their deaths. However, this man lets his mind slip and allows himself to be persuaded and intimidated by a powerful and non-rational superhuman being. We should follow the path of Arjuna’s despondency and reject those who try to persuade us into committing acts of violence with irrational appeals to “duty” or “God”. When faced with evil consequences, we should take our reluctance seriously lest we end up like Arjuna, largely alone due to our own foolishness and in possession of a kingdom we never truly desired.

Follow up for those who think I’ve “missed the point.”

For those of you who say “but wait! The war was necessary and justified because Duryodhana was evil!”, please read the following in which I defend Duryodhana.