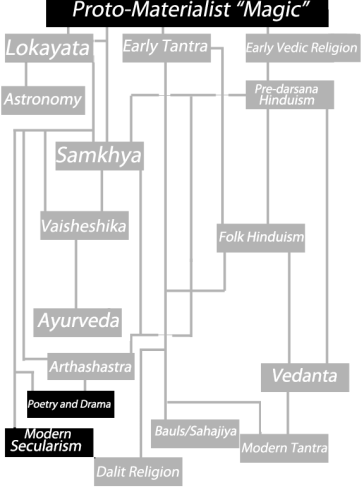

(Click to go back to Part I: Doctrines)

(Click to go back to Part II: Proto-Materialism in Vedic and Tantric Traditions)

(Click to go back to Part III: Orthodox Darshanas)

(Click to go back to Part IV: Social and Physical Sciences)

Culture:

Much of the cultural output from the Mayura to the Gupta period reflects the themes of Lokayata. Though it had always been prevalent amongst the population, as an aspect of Arthashastra, a pragmatic, syncretic permutation of Lokayata contributed to the ruling ideology. (1) Shastri is fully convinced of their influence:

“The Lokayatikas were a creed of joy, all sunny. Through their influence, at that period of Indian history [broadly speaking, 200 BC – 400 CE], the temple and the court, poetry and art, delighted in sensuousness. Eroticism prevailed all over the country. The Brahmin and the Chandala, the king and the beggar took part with equal enthusiasm in Madanotsava, in which Madana or Kama was worshipped. Reverences to this festival are not rare in works of poets like Kalidasa, Bisakha, Datta and Sreeharsa.” (2)

Illustration depicting a scene from a Kalidasa poem. This type of erotic content is fairly standard for poetry of this period. The poem and image source are Joshiartist.com

Poetry of this period communicates the earthly, pleasure oriented, anti-clerical ethos extremely well. What follows are four representative samples of poetry from the era of Lokayata’s greatest influence:

Who was artificer at her creation?

Was it the moon, bestowing its own charm?

Was it the graceful month of spring, itself?

Compact with love, a garden full of flowers?

That ancient saint there, sitting in his trance,

Bemused by prayers and dull theology,

Cares naught for beauty: how could he create

Such loveliness, the old religious fool?

–Kalidasa (3)