“Birth is misery, old age is misery, and so are disease and death, and indeed, nothing but misery is Samsâra, in which men suffer distress.” -Mahavira, Uttarâdhyayana Sûtra, Lecture 19, Verse 15.

***SPOILER ALERT***

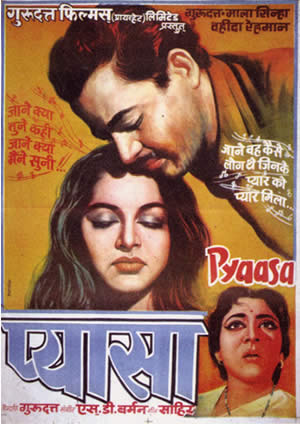

Pyaasa movie poster depicting Vijay (Guru Dutt), and Gulabo (Waheeda Rahman) in the center, with Meena (Mala Sinha) looking on unhappily from the corner. This poster kind of gives away the resolution of the love triangle.

Image source: A Tangle of WiresThe full movie is available on Youtube. Click the “CC” button to access english subtitles.

This is probably the most beautiful, poetic Bollywood film I’ve seen to date. For what it’s worth, Time Magazine agrees that its one of the best in cinema history. You really should watch it for yourself, but not everyone has a 2 hour commitment. So just read the post instead. You’ll feel like you saw it. A small amount of summarization will be necessary here, but go to Wikipedia for an actual summary.

If you are just interested in the songs, they’ll be collected at the bottom of the article with the relevant Youtube links. (you might have to hit “Continue reading” if coming from the main page.)

The Saraswati River Runs Dry: The film starts out in a metaphorical Garden of Eden, (or should I say the Saraswati valley?) Vijay is peacefully lying down next to a river in a garden, and celebrating the beauty of nature in song. Within the first minute, the dreamy mood is broken by an anonymous leather shoe, which crushes a bumblebee before Vijay’s eyes and shatters the serenity of the moment. As he exits the park, Vijay ends the song by rhetorically asking: “What little have I to add to this splendor, save a few tears, a few sighs?”

The Eden analogy is apt because never again (on the story’s timeline) does Vijay sing a happy word of poetry. From here on, the story inhabits the corrupt material realm of fallen man.

Socialist Pipe Dreams:

“We have to build the noble mansion of free India where all her children may dwell. The appointed day has come – the day appointed by destiny – and India stands forth again, after long slumber and struggle, awake, vital, free and independent.” –Jawaharlal Nehru in the speech “A Tryst with Destiny,” August 14 1947

Impressive words right? Nehru didn’t invent this ideology. He just voiced the common sentiment that independence would harken a glorious new era for India, in which political and social structures would be overhauled for the better. Here is another such quote by a prominent independence leader you might have heard of:

“In the democracy which I have envisaged, a democracy established by non-violence, there will be equal freedom for all. Everybody will be his own master. It is to join a struggle for such democracy that I invite you today. Once you realize this you will forget the differences between the Hindus and Muslims, and think of yourselves as Indians only, engaged in the common struggle for independence.” -Mahatma Gandhi from “Quit India speech”, August 8, 1942

The fantasy of being on the cusp of a socialist golden age was integral to Congress’ nationalist ideology. When the heralded changes never materialized, disenchantment, despair, and even disgust at the state of Indian society percolated through the national zeitgeist.

Instead of this idealized future, Vijay finds a society in which one’s humanity is only worth what it can fetch on the market. A society permeated by hypocrisy and cruelty, These characteristics are not unique to India, but given the high hopes engendered by the independence movement it is easy to see why some Indians reacted with such despair in the 1950s. Nehruvian socialism failed in its promises, and left India to bear the unmitigated social and economic realities of developing world capitalism. I would argue to the contrary that it intensified the harshness of those realities, but that is a topic fit for another post.

Actor and Director of the film, Guru Dutt looking angsty.

Despite the watermark, Image source: Bollywood Updates

Vijay the Marxist: More than anything else, the film’s social critique centers around the dehumanizing conditions of Indian “capitalism.” I refer to “capitalism” in quotations here, because India by no means had capitalism, as defenders of the free market would define it. Nehruvian socialism was quite distant from laissez-faire. The definition used here is the Marxist one: an economic system in which the means of production is owned privately rather than collectively, In the Marxist paradigm, capitalism leads to things like commodification, commodity fetishism, and the alienation of workers from their labor (and therefore from their humanity.)

(If on the main page, hit “Continue reading” to read more)