I’ve been reading this book called “The Periphery Strikes Back” by Udayon Misra. It examines the historical context behind secessionist movements in Assam and Nagaland. Here I am just going to voice my observations based on the first two chapters, which deal with Nagaland specifically.

Nagaland was largely left to govern itself under British rule, with minimal direct administration. However, this “ungovernment” was quite strict, as the Naga tribes were forcibly isolated from commerce and interaction with Assam and the lowland peoples. Despite this isolation, American Baptist missionaries arrived even before the independence movement, introducing Christianity. According to this text, the spread of Christianity—along with, to a lesser extent, modernist ideas and economic structures—disrupted traditional Naga tribal structures. This transformation fostered a more universalistic or individualistic (as opposed to tribal) perspective, ultimately allowing a distinct Naga national consciousness to emerge. In this sense, the very foundation of Naga national identity appears to be a product of colonialism. This is not to imply that tribalism totally evaporated amongst the Naga, actually it continued to be a thorn in the side of the movement as we will see.

So it seems like there really isn’t really a primordially authentic Naga identity. I mean, it is authentic in the sense that that’s how it actually developed historically, and I’m not doubting the actual nationalist aspirations of existing Naga people. But the collective identity itself is a direct and simple product of colonialism. Of course this is true of many modern national identities, but I think that that’s worth pointing out and worth observing, because oftentimes, nationalistic identities and movements, including the Naga nationalist movement, appeals to a sort of primordialism, as though they are just expressing something that was always latent there in that people, but that’s obviously not true in the case of the Naga people, which had to undergo dramatic imposed external change in order to enter the space of nationalism at all, and which would naturally be a highly divided group of infighting tribes (they dont even share the same language).

Once the Naga identity fully emerged, (just in advance of the Indian independence movement) and began engaging with politics, its initial interactions were closely tied to the British colonial presence. The nascent Naga leadership initially sought to prolong British rule in India, positioning themselves as willing collaborators. Even as the British prepared to leave, the Nagas advocated for a special status as a British mandate rather than making any motion towards integrating into the newly independent Indian state. However, once India gained independence, the Naga movement quickly shifted toward secession. Given this trajectory, it is understandable why India would perceive the Naga struggle with extreme skepticism, as astroturfed, externally influenced, and potentially viewing it as a secessionist movement aligned with foreign interests rather than an organic nationalist uprising.

The Naga National Council (NNC), the precursor to the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), adopted a rigid stance in its negotiations with the Indian government, prioritizing complete independence over any form of autonomy. India too was somewhat intransigent insofar as they were equally unwilling to entertain total independence, but given their relative geopolitical position, this is to be expected and the Nagas were irrationally rigid for not accepting the reality of the situation. Despite India’s offers of varying degrees of self-governance, the NNC remained unwilling to compromise, viewing independence as non-negotiable.

According to the text, the Naga independence movement under the Naga National Council (NNC) differed significantly from most other tribal nationalist movements in Northeast India. Unlike groups such as the Kukis and Mizos, who were more willing to negotiate settlements with the Indian state, the NNC remained steadfast in its radical demand for complete independence. This intransigence appears to have been at least initially driven by its alignment with traditional tribal elders and conservative elements within the Naga community who were willing to back an openly hostile stance, and which were essentially the post-apocalyptic fallout Christianized elite class remaining from Nagaland’s transformation from its traditional tribal system into the one ruled by the NNC. Additionally, the influence of the key charismatic radical personality of Angami Zapu Phizo may have further reinforced this uncompromising position. In contrast, other tribal nationalist movements in the region were more pragmatic, engaging in negotiations that ultimately led to settlements with the Indian government. This certainly marks the Naga as somewhat unique.

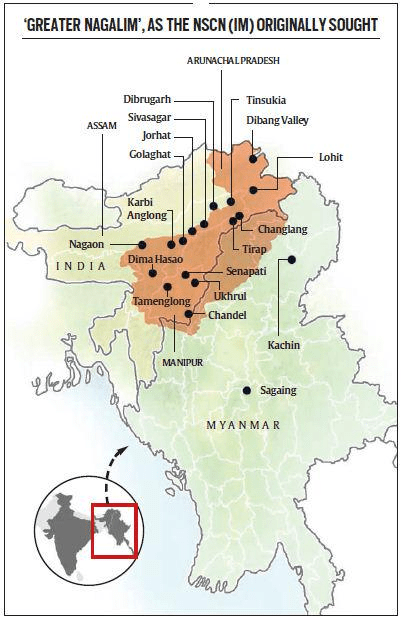

Despite his leadership, Angami Zapu Phizo was unable to completely overcome tribal divisions within the Naga independence movement. As a member of the Angami tribe, he was perceived as favoring his own tribal group, which limited his ability to unify the broader Naga community. This issue persisted beyond the NNC, as the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) also struggled to bridge tribal differences and work effectively with other secessionist movements in the Northeast. The text at least partially attributes this to Phizu’s initial gamble in empowering tribal elders in the NNC. This bolstered their relative position in Naga nationalist politics and allowed them to play out inter-tribal conflicts within the politics of Naga nationalism (albeit in a more coherent framework than a hundred years prior). Other tribes which went through a modernizing process tended to do so via the assimilation and empowerment of some sort of middle class into the Indian nation state, which ended up being the driving class of their nationalisms, and a more cohesive and pragmatic class at that. The inability to form a cohesive front or establish strong alliances with other tribal nationalist groups (and in fact, the neo-tribal antagonization of those groups as expressed by claiming their territory and attacking their camps) weakened the collective bargaining power of the Nagas.

I will continue reading, and perhaps give an additional update if further things about the text are worth remarking upon or remembering.