The Ahl-i-Hadiths, Deobandis, and Barelvis engaged in a series of debates with one another over the course of the late 19th century which illustrated three sets of varying doctrinal positions. This is based on a series of thoughts I’ve taken notes on over the course of a few years reading the books and journal articles in the bottom of this section. I will try to touch upon the social background of each sect in turn, and then briefly summarize what some of their more important doctrinal differences were. I am forced to discuss doctrine for the simple reason that it is what these sects’ writers wrote most about, and it is what the scholars who study them continue write most about. However, I think that this focus on doctrinal minutia can easily mislead us from observing the more practically relevant characteristics which distinguished them from one another, namely their strategies for dealing with the colonial encounter.

Some Background:

Before delving into the differences it is necessary to make a few remarks on the common context of defeat which all three sects shared. One piece of context is the failure of the Wahabee jihads in the earlier part of the 19th century, a piece of background which almost nobody talks about for some reason. Syed Ahmad Barelvi (not to be confused with the later Barelvi movement) led a jihad against British rule, Sikh rule, and local Muslim rulers whom he considered un-Islamic. His movement gained traction in the 1820s and 1830s, particularly in northwestern India (modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan). The goal was to establish an Islamic state based on strict adherence to the Quran and Hadith. He fought against the Sikh Empire under Ranjit Singh but was ultimately killed in 1831 at the Battle of Balakot. So that failed.

A second failure is the failure of the 1856 mutiny the Muslim ulema was starkly confronted with the weakness of their position in the post-Mughal political environment. As a whole they attributed the decline of Muslim power not to a political failure or to technological factors, but rather to a failure to live as proper Muslims. It was the desire to revive and reform true Islam amongst the Indian Muslims which constituted the overall driving motivation behind this spate of sectarian proliferation. Though all three groups were all philosophically anti-western and religiously conservative in the doctrinal sense, they were modern and “westernized” insofar as they made use of western cultural forms (education) and technologies (printing).

And then a third, which doesn’t require much elaboration, is just the overall failure of Muslim regimes to retain control over the Indian subcontinent in the first place, and their loss of sovereignty (including the end of their domination over Hindus and Sikhs) and subjugation by the British.

Shah Waliullah’s (1703–1762) school of thought is the ultimate progenitor of all three schools which I’ll be considering, though his ideas are advanced along different lines in each sect. On the one hand, it is true that Waliullah promoted the use of independent reasoning to analyze the Quran and Hadith, and wanted to make these texts more available without any commentary, at least to the Persian reading public. This is the part of his teaching which would be emphasized by the Deobandis and the Ahl-i-Hadis. On the other hand, he also valued the teachings of Islam’s historical intellectual and jurisprudential schools, and utilized them in his own Quranic interpretation. In addition, while he challenged some traditional Sufi practices, he was an overall supporter of Sufism and intended to reform rather than oppose Sufism. These are the aspects which would be emphasized by the Barelvi sect. He additionally enjoined his followers to adhere to Hanafi law in particular. On this point the Deobandis and Barelvis agreed (a rare occasion), while the Ahl-i-Hadis dissented. From this alone we can already see the general pattern forming: Barelvis adopt a more permissive traditionalist position, Ahl-i-Hadis adopt a conservative textualist position, and Deobandis adopt a conservative traditionalist position.

Now let us examine each school in turn.

Ahl-i-Hadiths:

The Ahl-i-Hadiths were founded in about 1880 by Syed Nazeer Husain Dehlawi. This group comprised of a much smaller and more elite population than the other two. They are also the most puritanical and fundamentalist. About one fifth of them were Sayyids, while the rest were largely descendants of Nawabs and eminent zamindars. They were patronized by what scarce Muslim nobility still remained in India. While not actually “Wahabi” (this term is used in so many confusing ways) in the Arabian sense, they did have the closest ties to the Wahabis of the Arabian peninsula, and the Muslim communities outside South Asia generally.

Their approach to saving Islam from the crisis of colonialism was an emphasis on piety and adherence to the untainted original scriptures. It is this effort to remain pure in their interpretation which lead them to rejecting the authority of all the juridical schools, along with the rest of the classical Islamic philosophical tradition which had influences from Greek and Babylonian thought. After all, if these traditions were so valuable then whey had they failed to prevent the current crisis? This rejection was a distinctly and characteristically modern divergence from nearly all preceding forms of Islam, with some notable exceptions or close comparisons like the Zahiri school or the Almohads. Not only the academic, but also militant features in post-Waliullah thought are visible in the Ahl-i-Hadiths. They did not reject violent Jihad out of principle, but rather argued in a written tract by Moulvi Abu Said Mohammed Husain that the conditions for a Quranicaly sanctioned jihad did not exist in the particular case of 19th century India under British rule. They were careful to translate this “Treatise on Jihad” into English and even dedicate it to the British lieutenant governor. However, when writing in Urdu, the jihadi language of militance was retained but shifted towards “the pen,” as when Maulavi Muhammed Husain Batalvi presciently wrote: “Brethern! The age of the sword is no more. Now instead of the sword it is necessary to wield the pen. How can the sword come into the hands of the Muslims when they have no hands. They have no national identity or existence…” Thus we see that the Ahl-i-Hadis are characterized by their intensity and their focus on purity of Islamic belief and practice. Proselytizing was of course an element of their strategy, but if the message was corrupt then proselytizing it would be useless. Thus their response was the most politically quietist and internal, with a focus on maintaining a purity of doctrine, practice, and belief.

Deobandis:

The Deobandis are very similar to the Ahl-i-Hadiths in terms of doctrine, but their more salient differentiating feature is their method. They are connected to the Waliullah line through Delhi College, where many of the founders, particularly Qasim Nanutwi and Rashid Ahmad studied. Those two (amongst others) later went on to found the modern madrassa at Deoband in 1867, which makes them the earliest of the three schools under discussion. Deobandis comprised a larger segment of the population than the Ahl-i-Hadis, but not as large as the third group, the Barelvis. Deobandis were also not as socially elite as the Ahl-i-Hadis, but were still led by upper class ulema. Their primary concern was to strengthen the ulema, but their adherents spanned all social classes, though with a large middle to middle-upper class component. They attracted followers because of their strident, yet comparatively moderate position (vis-a-vis the Ahl-i-Hadis), their modern and inventive style, and their intellectual and institutional independence from British control.

While almost as conservative as the Ahl-i-Hadiths in their doctrines, they placed a stronger emphasis on modern formal education and were more influential in the field of print. Qasim Nanutwi had been familiar with printing since his student days in Delhi when he worked at a printing press, and was quick to join the burgeoning print scene. Aside from print, they also pioneered the Islamic use of western organizational methods such as holding conferences and keeping minutes. The Deobandi pattern of modern schools, conferences, public and printed proselytization, etc. was impressive and impactful enough that it was eventually mimicked by the other two groups. In terms of academic content they drew influence both from Waliullah line of thought, and the Firangi Mahal school. Other than the acceptance of the Hanafi school, and acceptance of a wider range of Sufi traditions, there is little to doctrinally distinguish them from the Ahl-i-Hadiths. Not that this prevented the two groups from condemning one another in the harshest terms. Ultimately, their response to the crisis on the subcontinent was a technocratic or institutional effort to preserve the ulema and expand its influence under conditions of colonial subjugation. Interesting perhaps to modern readers– just google Deobandi Taliban or read this NPR article. Yeah, this is the root of that ideology as well.

Barelvis:

by 1890 the Barelvis had finally come onto the scene. They were founded and initially led by the charismatic Ahmad Raza Khan. Their membership was larger and generally socially inferior to the other two. Even their ulema leadership consisted of urban Pathans (as opposed to Sayyids), while their main membership base was the rural peasantry. Their doctrines were much less tolerant of individual ijtihad (basically, the reasoning and inquiry process which leads to legal interpretation) than the other two. Instead they reified the distinct spiritual hierarchy which was familiar to the rural masses, almost resembling Catholicism in some ways. In this intercessionary hierarchy the laity were placed the bottom. Pirs, holy men, and Islamic scholars were located at an intermediate position (with Khan himself at the top of this level). The companions of the prophet were above them, followed by the semi-divine Prophet Muhammed and of course God at the top of the hierarchy.

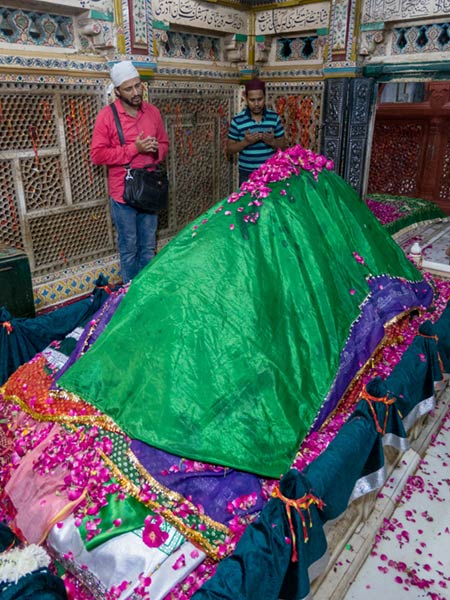

While still advocating the reform of folk practices which they felt were anti-Quranic, the Barelvis nevertheless supported those practices which were extra-Quranic. This entailed a theological defense of intercession by holy men, various extra-Quranic rituals, and the playing of qawali music. Holy men (and the super human Prophet) were said to have a conscious existence in the grave, and thus beseeching them was considered efficacious and not condemned as a form of idolatry. They were the only group of the three to which the pejorative label of “Wahabee” really has no application. Ultimately, their favored response to the crisis of the period was to rhetorically defend Islam as it had evolved over time, and to create an organizational unity out of the rural masses and their shrines which would protect them from the influence of the more puritanical schools. Unlike the other two schools, the fact that their iteration of Islam differed somewhat from the Islam of Muhammed’s time did not strike them as necessarily problematic. This is why the Barelvis only arose after the other two groups. Their original impetus was to defend a more “folk” iteration of Islam from the iconoclasm of the other reformers. Their basic response to colonialism was a retreat into and reification of folk practice, and an effort to structure and cohere it into something more unified, akin to the effort to create a “Hinduism” out of the disparate traditions of India.

Some further thoughts:

A natural materialist impulse is to attempt to discern differing economic interests among the groups as an explanation for their mutual hostility and ideological differences. It can be easily observed that the class ranking and degree of orthodoxy correlate across sects. Both social rank and orthodoxy were lowest amongst the Barelvis, intermediate amongst the Deobandis and high amongst Ahl-i-Hadis. But while this initially appears to be an interesting correlation, it is hard to get a ton of mileage out of this for further analysis because it is easily explained by contingent factors. The Indian peasantry of the Barelvi school consisted of relatively recent and incompletely converted Muslims. Their religion was consequently rife with folk practices. Barelvi doctrine reflected this. The Ashraf of the Ahl-i-Hadi and the Deoband leadership on the other hand descended from immigrants, or those close to the centers of Muslim authority. They were either Sayyids, or had close personal ties to the ulema. Orthodoxy was long established in their leadership communities. The slightly more moderate position of the Deobandis is probably explained by their pragmatic desire to actually gain adherents from the general population. Beyond this, a class analysis falls flat. The conflicts between the groups seem almost entirely doctrinal in nature, with no group forming a discrete political stance reflective of class politics until well after this period. The Barelvis lack the pro-peasant anti-zamindar flair which the Faraizis displayed in Bengal for example, in a distinct historical episode with a strongly class oriented explanation. The Deobandis’ social origins in the ulema class explain their doctrines and strategy, but it is not obvious to me that they were motivated by class interests as opposed to ideology. Equally perplexing from a class reductionist point of view, the ever idealistic Ahl-i-Hadis showed no real effort to protect or expand any aristocratic privileges which they still retained. Rather than emerging from conflicts inherent in the production relationship, these superstructure doctrinal differences seem to be not much more than intellectual exercises in adapting prior conceptions of Islam to new conditions. Class is therefore useful in estimating the relationship between social origins and doctrines, but nothing more pressing in terms of contemporary political or economic demands.

Another tempting impulse is to discern which differences are most salient with relation to how these schools impacted later events like the Pakistan movement or the growth of the Muslim League. But the connection here is too distant to be meaningful in the 19th century context. Their political programs were still too indistinct to be seen as forerunners of any later political movement. The connection to nationalism is not totally spurious however. These movements transformed the Indian ummah into a reading public, or more accurately multiple overlapping publics. This is often seen as a precondition for nationalism. However, this was essentially a joint project of all three schools and tells us little about what meaningfully distinguished them from one another.

Sectarian analysis I think is probably the more fruitful concept to apply in this situation. Conservative reformist sects rapidly proliferated in the 19th century Muslim world from Sudan, to Lebanon, to Tajikistan. (Similar scenarios played out concurrently within Russian and Irish Christianity, and of course among the neighboring Hindus, but the analogy there is much weaker.) These sects frequently contested their colonial authorities with violence as the earlier Wahabees had done. It is not unreasonable to surmise that if the defeats of the Wahabee campaign and the Mutiny had not been so severe, that perhaps the Ahl-i-Hadis or the Deobandis would have continued in the general trend of violent opposition. In this light, viewing the Barelvis, Deobandis or Ahl-i-Hadis as proto-nationalism is even less convincing, as Muslim sects of this period demonstrate the potential for many outcomes other than nationalism ranging from infighting (preventing the formation of nationalism) to abstention from politics, to persistent collaboration with the colonial state. This era of Indian muslim sectarianism can be read as part of a global Muslim response to the crisis of colonial subjugation by foreign powers. If the shared impetus for these sects was to respond adequately to the colonial threat (in a mostly pre-nationalistic era), then the salient sectarian differences are doctrinal in a sense, but are also strategic or tactical, with the object of these strategies being the strengthening or spreading of Islam even given the series of repeated recent historical failures to do just that within the subcontinent. Or to at least stop the bleeding. The Barelvis thought that the Muslim community was to be saved by adhering to its Quranicaly valid evolved traditions, and sustaining the hierarchical rural religious order, not by erasing the past. For them, the British and their iconoclastic peers were both threats to true Islam. The Deobandis concentrated on the pragmatic objective of institution building, strengthening the ulema and enlightening the ummah. Their strategy was technocratic and practical. The Ahl-i-Hadis were perhaps the most idealistic of the three. They concentrated on maintaining strength through Quranic purity, which also entailed fostering relationships with like minded sects in the Arab world and beyond. In comparison with these differences, the interminable debates concerning whether or not the Prophet had a shadow are interesting, but historically mostly irrelevant to what came next, and what their lasting impact was on the subcontinent.

Bibliography

Abdullaev, Kamoludin and Shahram Akbarzaheh, Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan .Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2010.

Behuria, Ashok K. “Sects Within Sect: The Case of Deobandi–Barelvi Encounter in Pakistan.” Strategic Analysis 32.1 (2008): 57-80.

Brown, Daniel W. Rethinking Tradition in Modern Islamic Thought, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Commons, David. The Wahabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. London: I.B. Tauris, 2006.

Hirst, Catherine. Religion Politics and Violence in 19th-Century Belfast. Dublin: Four Courts, 2002.

Husain, Moulvi Abu Said Mohammed. A Treatise on Jihad. Lahore: Karam Baksh, 1887.

Klibanov, Aleksandr Ilʹich. History of Religious Sectarianism in Russia: 1860s-1917. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1982.

Makdisi, Ussama. The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Malik, Bashir Ahmad. “Ijtihad Islam and the Modern World.” DA diss. St. John’s University, 2002.

Metcalf, Barbara D. Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860-1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982.

Mohammad, Maulana Hafiz Sher. The Ahmadiyya Case. translated by Zahid Aziz. Lahore: Ahmadiyya Association for the Propagation of Islam, 1987.

Muztar, A. D. Shah Wali Allah: A Saint-scholar of Muslim India. Islamabad: National Commission on Historical and Cultural Research, 1979.

Nault, Derrick M. Development in Asia: Interdisciplinary, Post-neoliberal, and Transnational Perspec tives, Boca Raton: BrownWalker Press, 2009.

Sanyal, Usha. Devotional Islam and Politics in British India: Ahmad Riza Khan Barelwi and His Move ment 1870-1920. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Shahid, Amir Khan. “Displacement of Shah Waliullah’s Movement and its Impact on Northern Indian Muslim Revivalist Thoughts.” Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan 51.2 (2014): 79-107.

Warburg, Gabriel. Islam, Sectarianism, and Politics in Sudan Since the Mahdiyya. Madison: The Univer sity of Wisconsin Press, 2003.

Zaidi, S.A. “Who is a Muslim? Identities of Exclusion−−North Indian Muslims, c. 1860−1900.” Indian Economic Social History Review 47 (2010): 205-229.