Here is an example of the style of painting which emerged in India under the British East India Company:

Great Indian Fruit Bat

Date: ca. 1777–82

Geography: India, Calcutta

Culture: Colonial British

Medium: Pencil, ink, and opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: Mat size: Ht. 27 1/4 in. (69.2 cm)

W. 35 1/2 in. (90.2 cm)

“In 1777, Sir Elijah Impey, chief justice of Bengal between 1774 and 1782, and his wife, Lady Mary, hired local artists to record the specimens of Indian flora and fauna they collected at their estate in Calcutta. Over the next five years, at least 326 paintings of plants, animals, and birds were made for the Impeys. On most of these works, the name of one of three artists—Bhawani Das, Shaykh Zayn al-Din, or Ram Das—appears along with the Hindi name of the animal and the phrase, in English, “In the collection of Lady Impey at Calcutta.” Although this painting bears no such inscription, it is closely related to another painting of a bat by Bhawani Das, and it has always been associated with Impey patronage. One can imagine Bhawani Das and the anonymous artist of this painting working side by side, observing the animals, but whereas Bhawani Das’ painting depicts a tawny-colored female bat centered on the page with both wings outstretched, his fellow artist has created an asymmetrical composition in shades of gray and black of an emphatically male bat with one wing dramatically unfurled.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Quite a looker isn’t he? I recently saw an interesting corner of the Metropolitan Museum of Art which I hadn’t seen before. It was a room labeled “Company Painting in Nineteenth-Century India.” For some reason I just hadn’t come across this room in prior wanderings. I decided to show you all some of the drawings and paintings I saw, with some historically related works interspersed for comparison.

The Company paintings are worthy of our notice because they reflect Indian aesthetic culture in this fascinating, relatively narrow slice of time between the Mughal state and the British state, when India was under Company rule. Mughal trained painters were able to modify their craft to suit British tastes, but this slight change put them (generally speaking) out of the genre of imaginative, decorative court art and into the genre of scientific sketches, administrative records, or more rarely, a sort of elite tourist kitsch. The Indian artists in this collection have been forced by circumstance to depict less conventionally beautiful plants and animals, and in a more realistic style. The cultural change from luxuriant Mughal court system into the impersonal knowledge aggregating machine of the colonial period is reflected in painting. Its pretty cool.

They are also fascinating because it shows us a period in Indian history where British artists suddenly join Hindus, Muslims in a shared aesthetic genre depicting the Indic subject matter. Take a look at these scientific drawings of plants for example:

Ashoka Tree Flower, Leaves, Pod, and Seed

-

Date: first half 19th century

Geography: India, probably Calcutta

Culture: Colonial British

Medium: Opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: Page: H. 23 1/4 in. (59.1 cm) W. 17 5/8 in. (44.8 cm)

“At the bottom of the page, the painting is inscribed Jonesia asoca, the Latin name for the tree commonly called Ashoka. Sanskrit for “without sorrow,” the term “Ashoka” refers to the bark’s reputed homeopathic properties for keeping women healthy. The tree itself is a rainforest tree prized for its foliage and fragrant flowers, which are carefully depicted here. As in the manner of scientific drawings, the branch is centered on the page, which has no background elements, and the pod and one of its seeds are shown in the top right corner. Three details of the flower are shown below, each labeled with letters and numbers and executed in shades of yellow, orange, and red.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Male Papaya Tree

-

Date: ca. 1790–1800

Geography: India, probably Calcutta

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Watercolor on paper

Dimensions: H: 29 3/4 in. (75.6 cm) W: 21 7/16 in (54.4 cm) Framed: H: 43 in (109.2 cm) W: 34 in (86.4 cm)

“The forests of India were among some of the richest resources of the British colonies, helping to increase interest in the study of natural history and scientific collecting. Primarily Indian artists worked for British patrons to draw the specimens as part of these studies. Major James Nathanial Rind (d. 1814), for whom this study was made, was commissioned into the Bengal Marines in 1778 and later transferred to the eighteenth native infantry. Between 1785 and 1789 he was based at Calcutta and was part of a group of officers involved in a survey of India. This botanical study depicts male flowers, the pollen from which can fertilize a nearby female flower and yield fruit.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A Radish Plant, Seed, and Flower

-

Date: late 18th century

Geography: India, Calcutta

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Ink and opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: H. 18 3/4 in. (47.6 cm) W. 24 1/2 (47.6 cm)

-

“This painting is from the collection of Major James Nathaniel Rind, an enthusiastic collector in India between 1778 and 1804. The unknown artist of this work has identified the specimen by way of the Persian writing on the right side of the page, which reads muli (radish), and has depicted it in three forms: as a plant, in its flowering form, and finally as a vegetable. This type, called “Rat Tail” or “Madras” radish (Raphanus caudatus), is bred especially for its pods, which appear more like green beans than the root radishes popular in North America.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Interestingly though, especially when it comes to the depiction of plants, this convergence of styles had long preceded the coming of British ships. For hundreds of years prior the Mughals were importing scientific drawings of flowers and learning to copy the style in order to produce decorative art. The following is a Belgian scientific drawing followed by an Indian decorative painting from a hundred years prior to Company rule :

Lilies, from Adriaen Collaert’s Florilegium, Antwerp, 1590, 555.d.23.(3.), pl. 6. (Source: British Library)

Lilies, signed by Mansur Jahangirshahi, c. 1605-12. From the Gulshan Album, Golestan Palace Library, Tehran, Ms 1663, p. 103. (Source: British Library)

So by the time the British arrived, Indians were already well versed in this style of drawing and painting. And yet under the Company that skill was recursively applied towards drawing producing the type of scientific drawings which inspired them the predecessors of these artists in the first place. Interesting how that works.

There is something slightly disturbing about these paintings as well. What makes them stand out to me as unusually beautiful is the combination of two contrasting aesthetic elements. Elements which happen to have been unified via the state/corporate violence of the British East India Company. The lush beauty of Indic plants and wildlife and the delicately soft watercolor technique contrasts with the rigid precision and sparseness which the Anglo mind craves in its pursuit of systemization and science. In many cases, the British artists here are acting as part of the colonization effort by cataloging the newly acquired company possessions. After all, something uncatalogued (and therefore not understood) might as well not exist. Similarly the Indian artists who eschew the impressionism and ostentation of the past while consciously adopting British artistic techniques are acting as collaborators. It is a role which they slide into quite readily. Almost too readily, as though the population is primed for subjugation as the orientalist trope goes. The comfort and speed with which the indigenous skill is adapted and turned towards the British eye is slightly embarrassing to someone with an emotive impulse towards Indian Nationalism. The shadow of empire hangs over these to remind the viewer that this meeting of cultures isn’t an entirely happy one.

As above, I’ll include some Mughal and other stuff in the photo scroll as well for the sake of comparison.

Image source is always the same as description source unless otherwise noted.

Enough with plants lets see some animals:

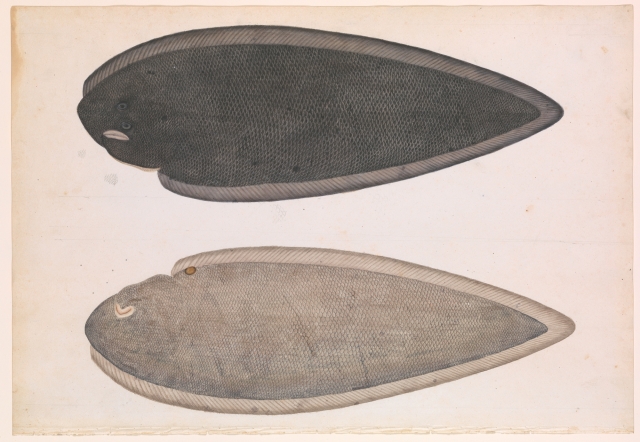

Two Sides of a Bengal River Fish

Date: ca. 1804

Geography: India, Calcutta

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Pencil, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Dimensions: Painting: H. 15 1/16 (38.3 cm)

W. 21 1/8 in. (53.7 cm)

Mat (Standard frame C): H. 22 1/4 (56.5 cm)

W. 28 1/8 in. (71.4 cm)

“This painting most likely illustrates a Bengal tongue sole fish (Cynoglossus cynoglossus), so-called for its unusual flat shape. The artist who created this work has illustrated two views—top and bottom—of the same creature, executed on paper in pencil and watercolor with traces of gilding. The mottled, scaly surface of the fish’s body is carefully rendered with a subtle metallic sheen, as are its mouth and eyes and the dark spots along the body.

The work is from the collection of Marquis Wellesley, governor-general of India between 1798 and 1805. His collection of natural history paintings numbered around 2,660 folios depicting plants, birds, mammals, insects, and fish. In his important position, Wellesley regularly received presents of rare flowers, birds, and animals from East India Company servants all over India and from travelers visiting from further east. The gifts were kept in a magnificent menagerie and recorded in paintings such as these.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Black Stork in a Landscape.

-

Date: ca. 1780

Geography: India, probably Lucknow

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Opaque watercolor on European paper

Dimensions: Painting: H. 21 1/2 in. (54.6 cm) W. 29 3/4in. (75.6cm) Mat: H. 35 1/2 in. (90.2 cm) W. 27 in. (68.6 cm)

“By the late eighteenth century, many Mughal-trained painters in central and eastern India were looking to the emerging British ruling class for patronage. The products of this new Company School were often albums of flora and fauna and other exotic sights of India, made to be taken back to Britain. Although this tradition reached its climax in the late eighteenth century, it continued well into the nineteenth. Of the varied subjects, bird studies, such as this bold depiction of a sturdy black stork, may be deemed a classic type. Paintings of birds, animals, and flowers had been an important genre in Indian art since the time of the Mughal emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–27), and the continuation of such subjects under British patronage was a natural extension of that established tradition, although the results were often quite different stylistically. In this painting, the stork is standing upright in a receding landscape of considerably reduced scale that contains a meandering river. The dramatic contrast in size between the bird and the vista it dominates gives the composition a distinctively idiosyncratic mood.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“The distinctive white neck feathers, purple-streaked wings, and red-tinged beak identify this tall bird as a woolly-necked stork (Ciconia episcopus), a native species of India known for its unusual plumage and height. The meandering watercourse on the right side of the composition could be a reference to the riverine areas in which such birds are typically found. A digit from the bird’s right foot rests upon its left, illustrating the artist’s close study of the standing position of these creatures. This work, like the image of the nightjar (2004.175) nearby, has been attributed to a set of 658 ornithological paintings commissioned by the French serviceman Claude Martin. (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

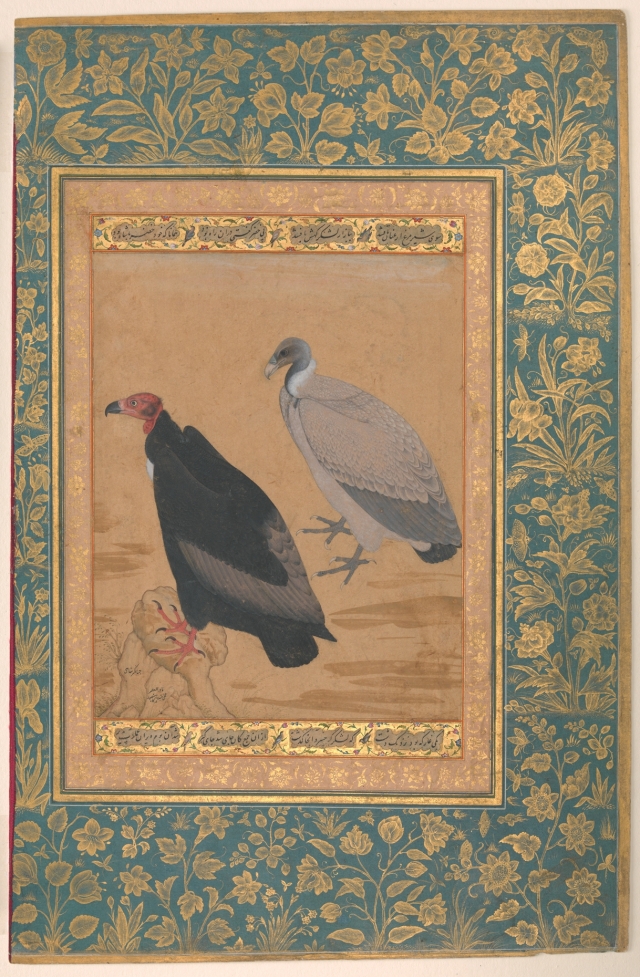

At the start I said this is interesting to me largely because of how you can see the evolution from prior art. Heres what I mean. Look at this Mughal depiction of a bird and how much more ornamented and expressive it is, while still (in this case) still being about as anatomically precise.

“Red-Headed Vulture and Long-Billed Vulture”, Folio from the Shah Jahan Album

-

Artist: Painting by Mansur (active ca. 1589–1626)

Calligrapher: Mir ‘Ali Haravi (d. ca. 1550)

Object Name: Album leaf

Date: verso: ca. 1615–20; recto: ca. 1535–45

Geography: India

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Dimensions: H. 15 3/8 in. (39.1 cm) W. 10 1/16 in. (25.6 cm)

The artist Mansur became such a master in painting flora and fauna that he received the title nadir al-‘asr, “rare one of the age.” Ornithologically accurate, the vultures as revealed by the brush of Mansur are far more than avian specimens. His masterful hand is evident in the subtle gradations of sooty hues and pearly beige and gray shades of the feathers. The sketchy rock suggestive of ground plane and the linear outline of the half-toned rock are not an actual habitat but a plausible setting out of the artist’s imagination. (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Back to the company drawings:

A Common Indian Nightjar (Caprimulgus asiaticus)

-

Date: ca. 1780

Geography: India, probably Lucknow

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: Painting: H. 18 5/8 in. (47.3 cm) W. 11 1/8 in. (28.3 cm) Mat: H. 27 in. (68.6 cm) W. 19 1/4 in. (48.9 cm)

“The classic works of the Company School of painting were studies of plant and animal life, of which this depiction of the nightjar bird is one. The bird is executed with great attention to detail—individual feathers have been outlined and painted with subtle gradations of color, and several shades of brown and black are used to delineate its body markings. The eye has a bright ring around it and the legs are textured with parallel line markings. The landscape in which the bird stands is only sparingly indicated, and is in a smaller scale than the animal. This feature is common in Company School paintings of this kind, as the main purpose of the painting was to record species new to British observers. The painting comes from an album made for Claud Martin (1735–1800), the French soldier and patron of the arts who settled in Lucknow in the eighteenth century.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“The Latin name for the nightjar, Caprimulgus asiaticus, translates as “goat sucker” and refers to the ancient myth that these sweet-looking birds sucked on the milk of goats by night. While untrue, nightjars probably got this reputation for the close contact they had with goats while feeding on nearby insects. The artist has paid particular attention to detail, rendering each feather individually and marking lines on the legs, while situating the bird in a perspectival landscape complete with tiny trees in the background. This painting comes from an album made for Claude Martin (1735–1800), a Frenchman in the service of Nawab Asaf al- Daula (r. 1775–97) and the East India Company in Lucknow. It subsequently belonged to the family of Charles Jenkinson, the 1st Earl of Liverpool.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Again here I’ll insert a Mughal painting of a bird for comparison:

“Spotted Forktail”, Folio from the Shah Jahan Album

-

Artist: Painting by Abu’l Hasan (Indian, born ca. 1588/89, active 1600–1628)

Calligrapher: Mir ‘Ali Haravi (d. ca. 1550)

Object Name: Album leaf

Date: recto: ca. 1610–15; verso ca. 1540

Geography: India

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on silk

Dimensions: H. 15 3/16 in. (38.6 cm) W. 10 3/8 in. (26.3 cm)

Jahangir (r. 1605–27) ordered this portrait of a spotted forktail from Abu’l Hasan, the artist upon whom he bestowed the honorific title “Wonder of the Age.” The inscription states that the emperor’s servants hunted this particular bird but does not say whether they killed it or merely captured it before it was portrayed. The silk ground adds a particular luster to the painting, further enhanced by the bird’s shiny eye, which contains glittering chips of a reflective material, probably mica. (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Back to the Company art, although this is a bit of a weird example because it actually does seem to have been purely decorative rather than part of a cataloging mission.

An Orange-Headed Ground Thrush and a Death’s-Head Moth on a Purple Ebony Orchid Branch

-

Artist: Shaikh Zain al–Din

Object Name: Illustrated album leaf

Date: dated 1778

Geography: India, Calcutta

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Opaque watercolor and ink on paper

Dimensions: Painting: H. 23.5 in. (59.7 cm) W. 31.5 in. (80 cm) Mat: H. 30 in. (76.2 cm) W. 40 in. (101.6 cm)

“This natural study comes from a famous collection of works commissioned by the Chief Justice of Bengal, Sir Elijah Impey, and his wife, Lady Mary. The original album included 326 paintings, many of which, like the one here, were distinctively inscribed in Persian with the name of the artist and in English in Lady Impey’s hand. This work has been signed by Shaikh Zain al-Din, and both inscriptions can be seen at lower left. Zain al-Din, who is considered the foremost artist to have worked on Impey’s album, is believed to have painted from life, which accounts for the naturalism of his work. The bird in this picture appears to step up on the branch of the Bauhinia purpurea, while the moth rests lightly on the flower to drink its nectar. Although he was trained in Mughal techniques, the absence of landscape and even ground color derives from European natural history paintings, indicating that the artist was also familiar with European prints.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

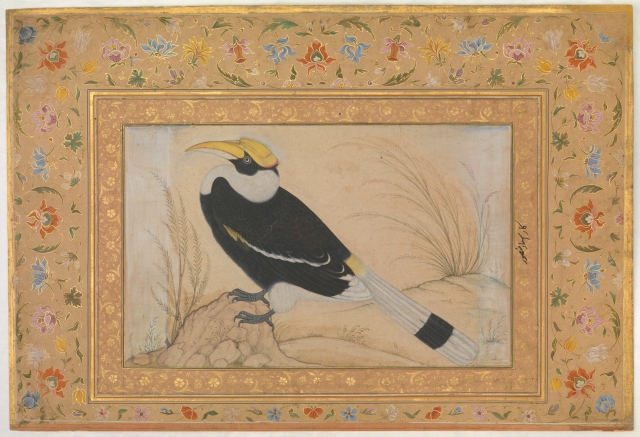

Even though that one was a decorative piece, I’ll still give another Mughal bird painting for comparison anyway:

“Great Hornbill”, Folio from the Shah Jahan Album

-

Artist: Painting by Mansur (active ca. 1589–1626)

Calligrapher: Mir ‘Ali Haravi (d. ca. 1550)

Object Name: Album leaf

Date: recto: ca. 1540; verso: ca. 1615–20

Geography: India

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Dimensions: H. 15 1/4 in. (38.7 cm) W. 10 1/2 in. (26.7 cm)

The emperor Jahangir’s memoirs record many of the animals he encountered while on his annual peregrinations, and the reasons he wanted studies of them to be painted. While we do not have such notes for this painting, we can imagine that Jahangir was intrigued by the creature’s size, with a wingspan of up to five feet, and by the loud droning noise it emitted, audible a mile away. (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Untitled

-

Date: ca. 1830

Culture: India, Company School

Medium: Ink on fabric

Dimensions: Image (sight): 15 1/2 x 19 1/4 in. (39.4 x 48.9 cm) Framed: 28 x 32 in. (71.1 x 81.3 cm)

(Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This one wasn’t actually on display (though a similar drawing was). Nothing much is written about it either (I don’t have the artist’s name. I suspect a British artist by the english writing in the lower right). But you can see how in the perspective, the sparseness of coloring and lack of people this more resembles formal British architectural or topographical studies than it does classical Indian depictions of architectural features.

For comparison, an older Indian work of Rajput design:

Maharana Ari Singh with His Courtiers Being Entertained at the Jagniwas Water Palace

-

Artist: Bhima , Indian

Artist: Kesu Ram (Indian)

Artist: Bhopa (Indian)

Artist: Nathu (Indian)

Date: dated 1767

Culture: India (Rajasthan, Mewar, Udaipur)

Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Dimensions: Page: 26 5/8 x 32 7/8 in. (67.6 x 83.5 cm) Image: 22 3/4 x 29 3/16 in. (57.8 x 74.1 cm)

“The maharana expresses his power and social position in this complicated work, which incorporates numerous figures set within the landscape of a lake palace. Employing multiple viewpoints, the painters depict Ari Singh in the main hall with his chiefs organized according to rank. They look on at a festival performance of dance and music. Ari Singh appears again in the lower left, next to a pool filled with fish and surrounded by tiny wall paintings populated with erotic scenes and the ten avatars (appearances) of Vishnu.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

More in the Company style:

Interior of the Taj Mahal Mausoleum

-

Date: early 19th century

Culture: India (Delhi or Agra)

Medium: Ink, tinted wash, and opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: Image (sight): 18 x 25 7/8 in. (45.7 x 65.7 cm) Framed: 26 x 34 in. (66 x 86.4 cm)

(Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Bara Imambara Complex at Lucknow

-

Date: ca. 1800

Geography: India, Lucknow

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Ink and opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: Painting: H. 22 1/8 in. (56.2 cm) W. 15 1/2 in. (39.4 cm)

“The unknown artist of this work has created a bird’s-eye view of the Bara Imambara complex in the style of a European topographical study. It is a valuable historical record of several parts of the site, which were demolished during the Indian uprising of 1857. The distant gardens and structures seen on the upper left, for example, no longer exist. The Bara Imambara, whose name means “big shrine,” comprises the massive congregational mosque (seen at an angle at the upper right) and several interlocking forecourts. It is an important place of worship for Shia Muslims, who celebrate the religious festival of Muharram. This massive structure was commis-sioned by Nawab Asaf al-Daula of Lucknow as part of a famine-relief project.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Again, I’ll show a Rajput miniature for comparison.

Escapade at Night:

-

Artist: Attributed to Chokha (Indian, active 1799–ca. 1826)

Date: ca. 1800–10

Culture: India (Rajasthan, Mewar)

Medium: Opaque watercolor, ink and gold on paper

Dimensions: Image: 11 1/2 x 14 7/8 in. (29.2 x 37.8 cm) Page: 12 3/16 x 15 15/16 in. (31 x 40.5 cm)

A nobleman ascends a rope to visit his lover, who reclines within the palace’s defended walls. The clandestine tryst is a theme that runs through the poetry of this period, and certainly the tension of this forbidden act would have appealed to royal tastes. Presenting this scene in the somber tones of night is an innovation of the artist Chokha, who followed his father, Bagta, as the major Mewar painter during this period. Chokha gives the painting a sense of drama by juxtaposing the quietude of the sleeping cows and guards with the brightly colored protagonists and a roiling band of black thunderclouds. (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Back to the Company style

Interior of the Hammam at the Red Fort, Delhi, Furnished According to English Taste

-

Date: ca. 1830–40

Geography: India, Delhi

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: H. 9 1/8 in. (23.2 cm) W. 12 1/8 in. (30.8cm)

“It was not unusual for the resident British of nineteenth-century Delhi to buy ruined or abandoned Mughal or Sultanate buildings and monuments, which they then converted from their original functions to habitable spaces. This painting illustrates the conversion of a hammam (bath house) into a living room, complete with a piano or harpsichord, a bench, and an assortment of glass bottles and other objects. The white floor inlaid with flower motifs resembles that of the hammam at the Red Fort in Delhi, where a British national had been installed by the early nineteenth century.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A Syce (Groom) Holding Two Carriage Horses

Artist: attributed to Shaikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya (active 1830s–40s)

Date: ca. 1845

Geography: India, Calcutta

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: H. 12 in. (30.5 cm)

W. 20 in. (50.8 cm)

“There is something hypnotic and disquieting about this near mirror image of a syce, or groom, flanked by almost identical horses. The artist has chosen a pictorial format whose power is as decorative as it is descriptive. The strict symmetry is relieved, however, by subtle differences in the sizes, proportions, and harnessing of the horses, as well as by slight left-right variations in the posture and dress of the groom. The darks are very dark and the lights very light, intensifying the decorative appeal of the composition. Although the color is severely restricted, the artist has beautifully realized the feel of Indian light, and the low horizon line makes both the space and the foreground trio appear truly monumental. The painting’s beauty and subtlety testify to the high quality that late Company School artists could attain.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Many of the East India Company officers who commissioned paintings during the nineteenth century sought a visual record of their own households, including animals, possessions, and servants. Shaikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya specialized in such paintings and depicted these subjects with a naturalism that is both dignified and poetic. In this work the artist has painted a syce, or groom, symmetrically flanked by almost identical horses.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

I hate to dwell on this particular painting for so long, but there are a number of interesting comparisons to be made. Firstly, although this concept of producing a “visual record of their own households” sounds pretty Anglo, the Mughals did it as well, at least for their most prized treasures:

Portrait of the Elephant ‘Alam Guman

-

Artist: Painting attributed to Bichitr (active ca. 1610–60)

Object Name: Illustrated album leaf

Date: ca. 1640

Geography: India

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Opaque watercolor and gold on paper

-

“Persian inscription (in nasta’liq script in gold cartouche, possibly in Shah Jahan’s hand): “Likeness of ‘Alam Guman Gajraj [the arrogant one of the earth, king of elephants] whose value is one lakh [a hundred thousand rupees]” Along with seventeen other elephants from Mewar, this famous tusker was presented to the Mughal emperor Jahangir during the New Year celebrations of March 21, 1614. In his memoirs, Jahangir states: “on the second day of the New Year, knowing it propitious for a ride, I mounted [‘Alam Guman] and scattered about much money.” Elephants were among the prized possession of the Indian courts, and their portraiture falls into the larger Mughal practice of meticulously recording the treasures of the court.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

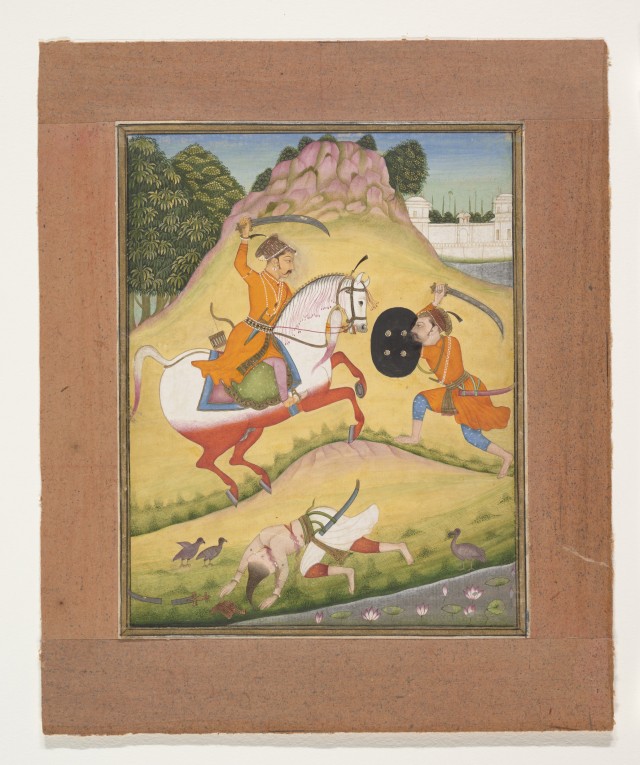

But I’d also like to show depictions of horses from prior eras, or from artists producing for Indian patrons. First a piece with Hindu subject matter, painted by a Muslim seemingly Rajput style but similar enough to the Mughal stuff. But I think it shows the generic pre-British horse depiction style:

Nata Ragina: Folio from a ragamala series (Garland of Musical Modes)

-

Artist: Mohamed (active early 18th century)

Date: 1714

Culture: India (Rajasthan, Bikaner)

Medium: Ink and opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: 6 x 4 3/4 in. (15.2 x 12.1 cm)

“Within the ragamala tradition the association of music, text, and image is not always obvious. In this instance, in accord with visualizing music in a heroic mode, a male figure is described in the text as “[g]ripping his sword [as] he moves about the field of battle.” Yet this text also refers to a ragini, making the musical mode feminine, and hence the protagonist should presumably be a woman. While there are examples of this scene with a woman dressed as a warrior, more often, as we see here, it is a male figure. Such contradictions are common within the ragamala genre.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

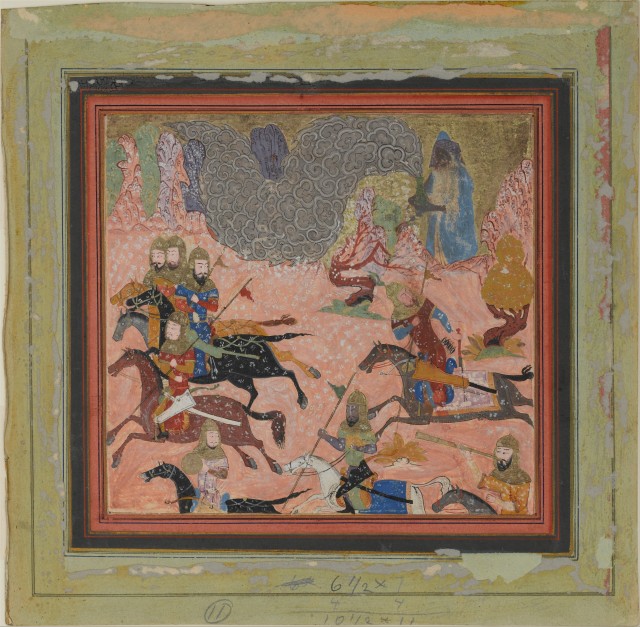

And then Zoroastrian subject matter from a (much earlier) Muslim kingdom, drawing more clearly from Persian miniature tradition. It shows a more primitive horse depiction style:

“Bazur, the Magician, Raises up Darkness and a Storm”, Folio from a Shahnama (Book of Kings)

-

Author: Abu’l Qasim Firdausi (935–1020)

Object Name: Folio from an illustrated manuscript

Date: ca. 1430–40

Geography: India

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Dimensions: 7.75 in. high 8.12 in. wide (19.7 cm high 20.6 cm wide)

“During a battle between the Iranians and the Turanians, a sorcerer named Bazur (shown here in a blue cape) climbs to the top of a mountain and creates a blizzard that engulfs the Iranian forces. In the ensuing confusion, the Turanians attack, causing heavy casualties.This painting comes from a copy of the highly Persianate Shahnama that was probably made in northern India. The paintings from this book were later cut out and placed in an album with brightly colored borders.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Sketch of a Horse

- Date: late 18th century

Culture: India (Pahari Hills)

Medium: Ink on paper

Dimensions: Image (sight): 8 x 9 1/2 in. (20.3 x 24.1 cm)

This formal and idealized representation of a horse is typical of Pahari workshops and readily distinguished from the more naturalistic and animated renderings seen in the Rajput painting tradition. (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

View of a Mosque and Gateway at Motijhil

Artist: Attributed to Sita Ram (active 1814–23)

Object Name: Illustrated single work

Date: ca. 1814–23

Geography: India, Bengal

Culture: Islamic

Medium: Opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: Painting: H. 13 in. (33 cm)

W. 19 1/4 in. (48.9 cm)

Mat (Standard size B): H. 16 in. (40.6 cm)

W. 22 in. (55.9 cm)

“The subject of this painting is the mosque and gateway of the Sang-i Dalan palace at Motijhil, outside Murshidabad, built in 1743 by Nawazish Muhammad Khan. The artist was probably Sita Ram, an accomplished Bengali painter. This work comes from an album that had been made for Francis Rawdon (second earl of Moira, later first marquess of Hastings; governor-general of Bengal 1813–23) on a tour of northern India.

Sita Ram’s career can be followed only for the brief but intense span of time when he worked for Hastings, from about 1814 to 1823. During that period, he created the ten albums of the 1814–15 journey and at least two more based on tours in 1817 and 1820–21; contributed to albums of natural history drawings; and made other studies that were later placed in scrapbooks.

Like the other works made for Hastings, this painting no doubt captures what the traveling party saw, but it also suffuses both landscape and architecture with a sense of languor, evoking a timeless mood rather than a fleeting moment from a trip. This impression is further emphasized by the artist’s decision to depict the Motijhil site from behind, excluding the main palace and emphasizing the state of decay of the remaining buildings.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Sitaram, the painter of this enchanting scene, was hired to record the travels of Francis Rawdon, the governor-general of Bengal between 1814 and 1821. The painting illustrates the Sang-i Dalan palace complex at Motijhil, Bengal, where the Rawdons traveled in 1817. The artist, working in the picturesque style, has chosen to depict the scene not by foregrounding the site’s majestic palace but rather by emphasizing a romanticized state of decay, with fallen debris from the nearby structures. In doing so, Sitaram creates a melancholic view suggesting a nostalgia for the Mughal Empire before the arrival of the British.” (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

So that one was produced by an Indian, but here are two later pieces by British artists (not in the Met) which are in a similar but with a more architectural and less atmospheric focus:

Lithograph of “The Great Temple at Bobaneswar,” from a sketch by James Fergusson. ~1840s (Source: The Victorian Web)

“Jaina Tower at Cheetore” from a sketch by James Fergusson. ~1850s (Source: The Victorian Web)

Well thats all I’ve got for you today.

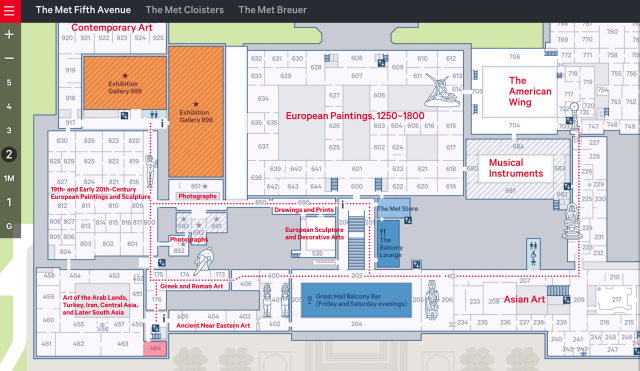

According to the museum map, the exhibit where I found most of these Company paintings is located here (bottom left, highlighted in pink). And the Mughal room is right next door:

If you are in New York at some point it is worth checking out. The Met has a lot of Indian art, this is just a small corner of it.

Also the museum didn’t pay me to do this, I just like it.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy something else I wrote on Indian painting, misleadingly titled “King Akbar’s Mahabharata, or the Razmnama (Book of Wars)” or a different art history essay on the transmission of Hindu and Buddhist deities to Japan entitled “Hindu Devas take a (silk) road trip to Japan!“

🕷🕷🕷🐠🐠🐠🐠🐜🐞🌶🍒🍌🍉🍎🍏🍐🍇

Sent from my iPhone

>

This is beautiful artwork. I appreciate having seen it.

Hello, Nick! Good to see you! These are exquisite and I shall make my way to MOMA soon as I can. Thank you! This is Roy from the now-defunct Outlands Community. Pay us a visit; you may not like our WP, which is fine; but be well and at peace regardless!

Glad to hear from you Roy, and glad to see that you are still active. Why wouldn’t I like your wordpress? Seems like a worthy creative venture 🙂 Also, remember that these paintings are at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, not the Museum of Modern Art. Otherwise you’ll be quite confused! (I get them mixed up all the time too).

Oopsie on MOMA! Welcome to OUR WP, then!

A day of rare luck I began to see your page with breathless wonder! I write a lot on these topics, two of my e-books are in Amazon Kindle, selling hot. I am just getting my current book through. Then I shall start my next book on Persian editions of Indian epics from Babarnama to post Jahangir epoch. I shall look forward to your assistance to download a few paintings of the Indian epics for inclusion in my next book. Warm regards, Sanujit Ghose E-mail sanujit40@gmail.com

Glad you enjoyed! These images should be pretty easy to download though. If you are having trouble shoot me an email. videshisutra@gmail.com I’d also like to see your books but was having some trouble finding them on Amazon.